Dammed

Landscapes

Landscapes

River Infrastructure at the Mississippi’s Headwaters

Research by Elaine Stokes with funding from the Penny White

Foundation at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design

︎︎︎

Project Summary

︎

This work serves as a case study for a broader dissertation on riparian infrastructure along the Mississippi River and the ethnographic relationships to these regulated landscapes. Within the Mississippi River Basin, contestation over water has transformed the ways humans and rivers interface with one another

This project studies dams constructed at the headwaters of the Mississippi as a critical example of infrastructure implemented to regulate downstream water levels at the expense of the Ojibwe people, who occupy the land surrounding the headwaters. The work was guided by interviews with individuals from the Ojibwe Division of Resource Management and the United States Army Corps of Engineers, as well as tours of the dams and canoe trips of the lakes and rivers the dams regulate.

Additionally, archival research at the Minnesota Historical Society and the Itasca County Historical Society supplemented findings from the sites visits. The archival documents included survey maps from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plotting out strategies to dredge both Leech Lake River and the Mississippi River on Leech Lake Reservation.

Through these methods, the research considers the ways federal infrastructure has impacted Ojibwe use of water and lands, and inversely, how Ojibwe land and water management strategies might influence dam management in the future.

— where once variability was accepted as part of riverine life, fixity and predetermination have become the new norm as water flows becomes regulated with locks, dams, levees, and reservoirs.

This project studies dams constructed at the headwaters of the Mississippi as a critical example of infrastructure implemented to regulate downstream water levels at the expense of the Ojibwe people, who occupy the land surrounding the headwaters. The work was guided by interviews with individuals from the Ojibwe Division of Resource Management and the United States Army Corps of Engineers, as well as tours of the dams and canoe trips of the lakes and rivers the dams regulate.

Additionally, archival research at the Minnesota Historical Society and the Itasca County Historical Society supplemented findings from the sites visits. The archival documents included survey maps from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plotting out strategies to dredge both Leech Lake River and the Mississippi River on Leech Lake Reservation.

Through these methods, the research considers the ways federal infrastructure has impacted Ojibwe use of water and lands, and inversely, how Ojibwe land and water management strategies might influence dam management in the future.

Focus Areas

The drawings, maps, and text shown here are the result of this site visit. They attempt to convey the experience of traveling through the Mississippi Headwaters while also tracking the impacts of dams on the lands and waters of the Ojibwe people.

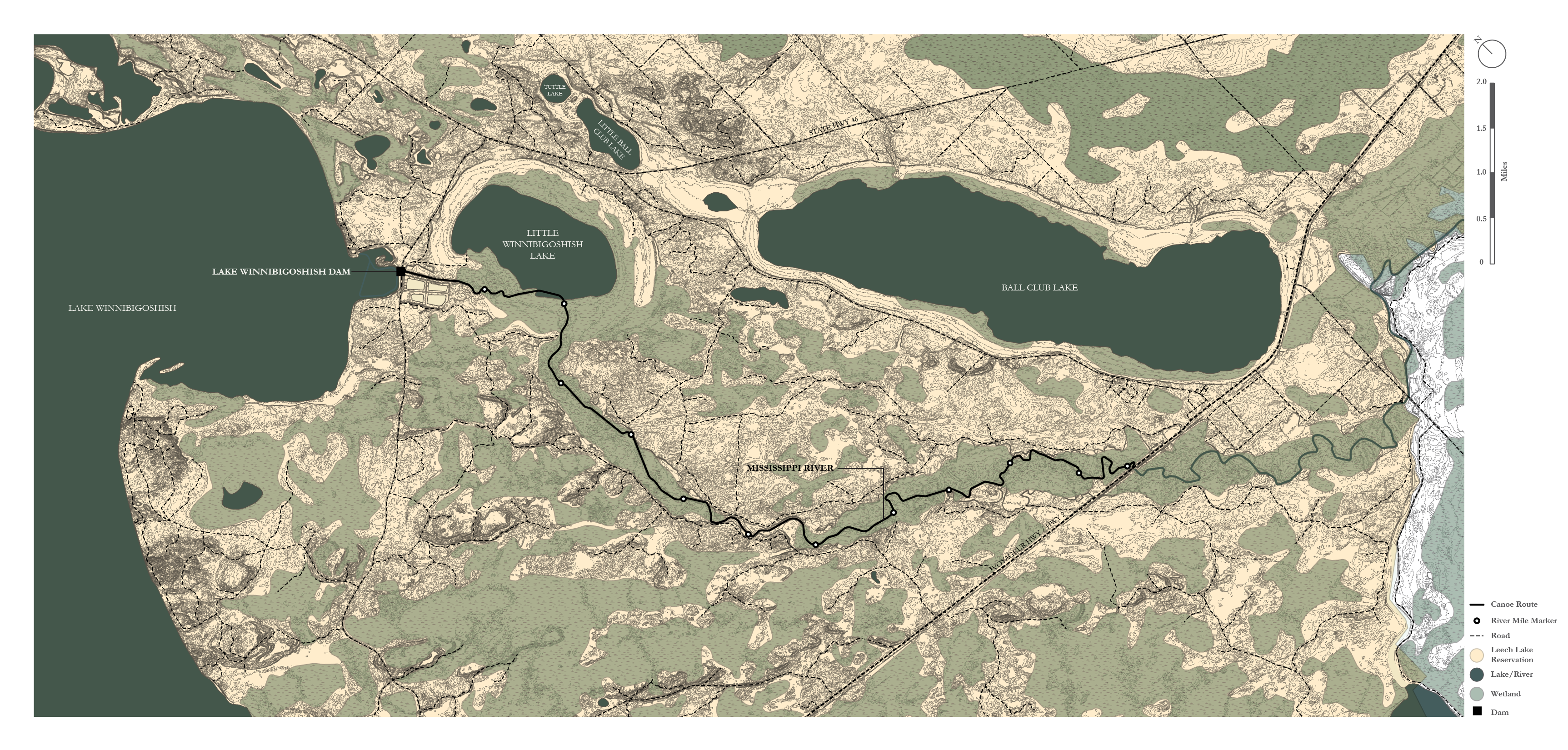

This work focuses on three dams: Leech Lake Dam, Winnibigoshish Dam, and Pokegama Dam. The first two lie within the boundaries of Leech Lake Reservation, while the latter rests outside the reservation but within 1855 Treaty territory. Each dam is owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and they were originally constructed to manage water flow downstream along the Mississippi to facilitate easier barge and ship traffic.

Through site visits and conversations, three themes regarding the dams and headwaters emerged: wild rice habitat, erosion, and dredging. These aspects of the landscape are ever-present along both Leech Lake River and the Mississippi River, and are expanded upon in other pages of this collection. Another topic that ties all dams together is their impact on pre-existing lakes, which now act as reservoirs.

This transformation of the landscape has impacted wild rice habitat and flooded innumerable sacred and archaeological sites with evidence of Anishinaabe livelihood. Mappings of this expansion can be seen in the series of three maps on each lake.

This work focuses on three dams: Leech Lake Dam, Winnibigoshish Dam, and Pokegama Dam. The first two lie within the boundaries of Leech Lake Reservation, while the latter rests outside the reservation but within 1855 Treaty territory. Each dam is owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and they were originally constructed to manage water flow downstream along the Mississippi to facilitate easier barge and ship traffic.

Through site visits and conversations, three themes regarding the dams and headwaters emerged: wild rice habitat, erosion, and dredging. These aspects of the landscape are ever-present along both Leech Lake River and the Mississippi River, and are expanded upon in other pages of this collection. Another topic that ties all dams together is their impact on pre-existing lakes, which now act as reservoirs.

Leech Lake, Winnibigoshish Lake, and Pokegama Lake (as well as many other lakes in the region) have expanded drastically as a result of the dams, flooding well over 100 square miles of land.

This transformation of the landscape has impacted wild rice habitat and flooded innumerable sacred and archaeological sites with evidence of Anishinaabe livelihood. Mappings of this expansion can be seen in the series of three maps on each lake.

Methods

Additionally, the history of dams and waterways in this region is intrinsically linked with forestry, and industry that has transformed the landscape and continues to threaten Ojibwe land use today. Here, I would like to disclose my own settler history within this region. My grandfather, Harold Zigmund, was an employee and eventually the president of Blandin Paper Mill, a processing plant that transformed trees into paper using power from a dam built on the Mississippi River. Given my family’s history in this place extracting resources and wealth from Ojibwe land, I fully acknowledge my complicity in the degradation of these lands, and hope this work can in a small way support the sovereignty of Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe.

The collection of works in “Dammed Landscapes” is also formatted as a mini-exhibition. Where the pages can be easily packed into a mailing box, and can then be unfolded and assembled in a variety of configurations. The hope is that the information shared here can be informative and, rather than living packed away on a shelf, can easily be brought out and shared.

In essence, this project aims to expanded dialogues centered on Native American perspectives, connecting communities through visual and written narratives of the Mississippi River’s headwaters.

Project Sites

︎

Leech Lake Dam

Leech Lake Dam

Pokegama Dam

Winnibigoshish Dam

Originally Constructed 1882-1884

Major Repairs

1900-1903 — Timber abutments and bays were replaced by concrete

Operated & Maintained by The United States Army Corps of Engineers

Regulated Water Bodies

Leech Lake Dam controls water flow from Leech Lake, which flows into Leech Lake River.

Leech Lake River connects with the Mississippi River 27 miles downstream from the dam.

Leech Lake Dam and portions of Leech Lake lie within the Leech Lake Reservation boundaries.

Major Repairs

1900-1903 — Timber abutments and bays were replaced by concrete

Operated & Maintained by The United States Army Corps of Engineers

Regulated Water Bodies

Leech Lake Dam controls water flow from Leech Lake, which flows into Leech Lake River.

Leech Lake River connects with the Mississippi River 27 miles downstream from the dam.

Leech Lake Dam and portions of Leech Lake lie within the Leech Lake Reservation boundaries.

Originally Constructed 1882-1885

Major Repairs

1904 — concrete reconstruction

2011 — leaf gates installed and remaining sluiceways were reconstructed

Operated & Maintained by The United States Army Corps of Engineers

Regulated Water Bodies

Pokegama is located slightly upstream from Grand Rapids, MN and controls the Mississippi River prior to passing the town.

Pokegama Lake, Jay Gould Lake, Loon Lake, Long Lake, and Cut-Off Lake are immediately upstream of the dam.

Pokegama Dam and the entirety of Lake Winnibigoshish lie within the 1855 Treaty boundaries, where Ojibwe people argue they have the right to hunt, fish and gather. This right has been recognized for other treaty lands in Minnesota and Wisconsin by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Major Repairs

1904 — concrete reconstruction

2011 — leaf gates installed and remaining sluiceways were reconstructed

Operated & Maintained by The United States Army Corps of Engineers

Regulated Water Bodies

Pokegama is located slightly upstream from Grand Rapids, MN and controls the Mississippi River prior to passing the town.

Pokegama Lake, Jay Gould Lake, Loon Lake, Long Lake, and Cut-Off Lake are immediately upstream of the dam.

Pokegama Dam and the entirety of Lake Winnibigoshish lie within the 1855 Treaty boundaries, where Ojibwe people argue they have the right to hunt, fish and gather. This right has been recognized for other treaty lands in Minnesota and Wisconsin by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Originally Constructed 1881-1884

Major Repairs

1899-1900 — concrete bulkheads replaced the timber stop logs and gates

1912 — a fishway was constructed (no longer in use)

Operated & Maintained by The United States Army Corps of Engineers

Regulated Water Bodies

Winnibigoshish Dam controls water flow from 28 lakes upstream of the dam, including Lake Winnibigoshish.

The Mississippi River originates in these lakes and flows through the dam.

Winnibigoshish Dam and the entirety of Lake Winnibigoshish lie within the Leech Lake Reservation boundaries.

Major Repairs

1899-1900 — concrete bulkheads replaced the timber stop logs and gates

1912 — a fishway was constructed (no longer in use)

Operated & Maintained by The United States Army Corps of Engineers

Regulated Water Bodies

Winnibigoshish Dam controls water flow from 28 lakes upstream of the dam, including Lake Winnibigoshish.

The Mississippi River originates in these lakes and flows through the dam.

Winnibigoshish Dam and the entirety of Lake Winnibigoshish lie within the Leech Lake Reservation boundaries.

Travel Routes

︎

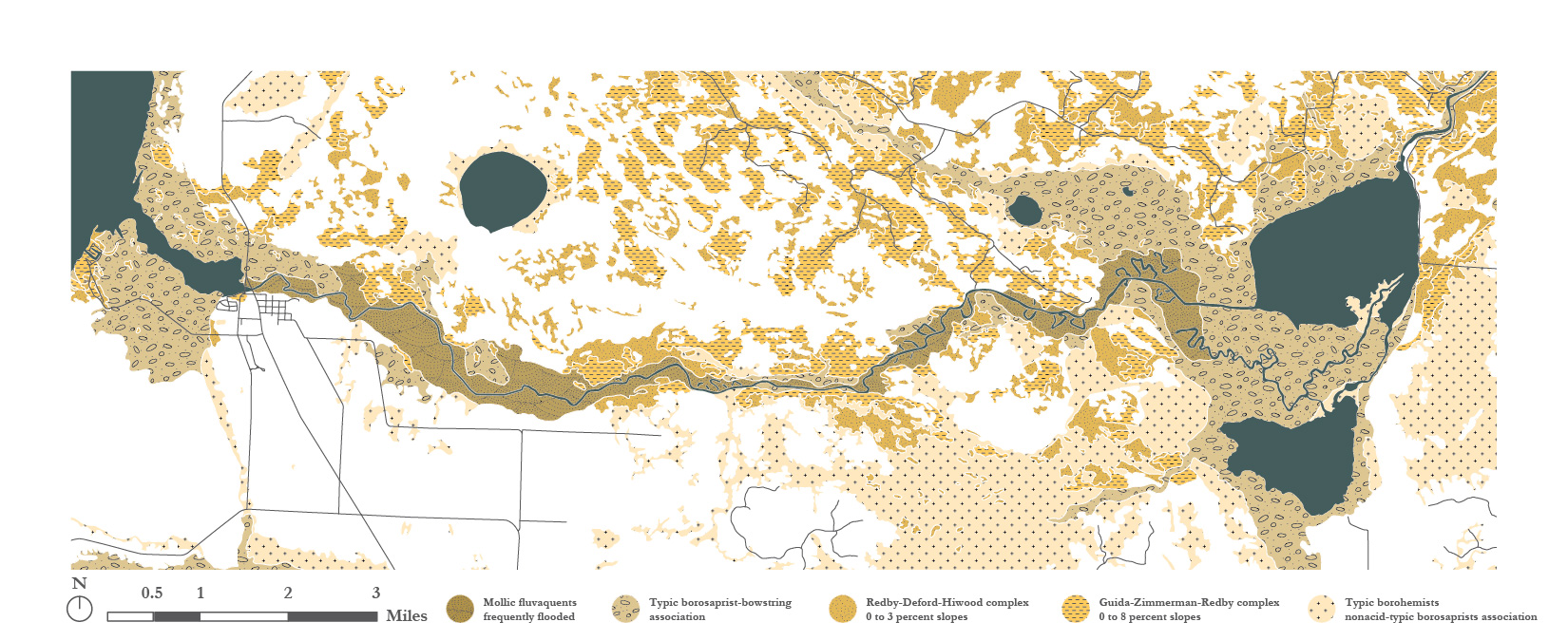

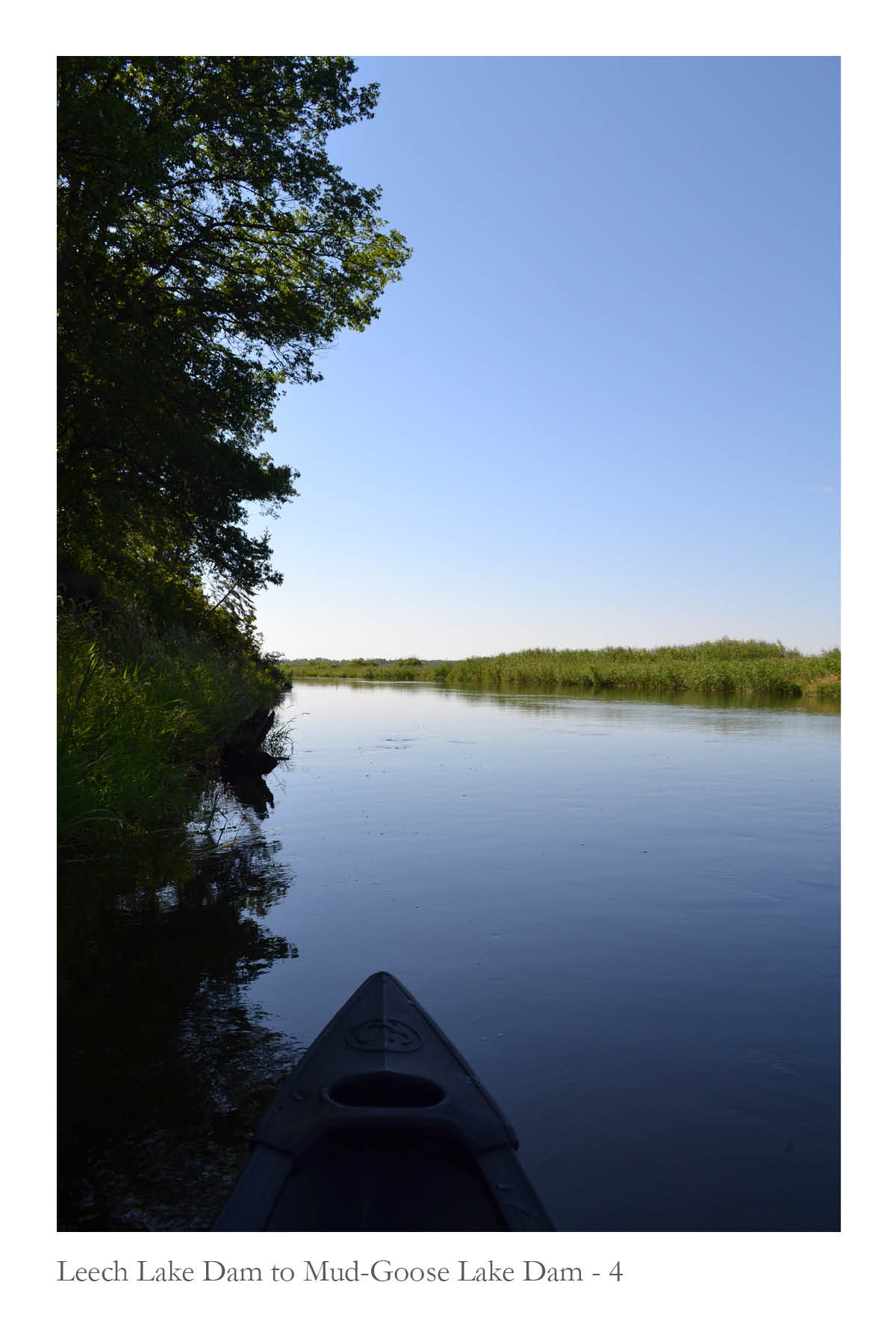

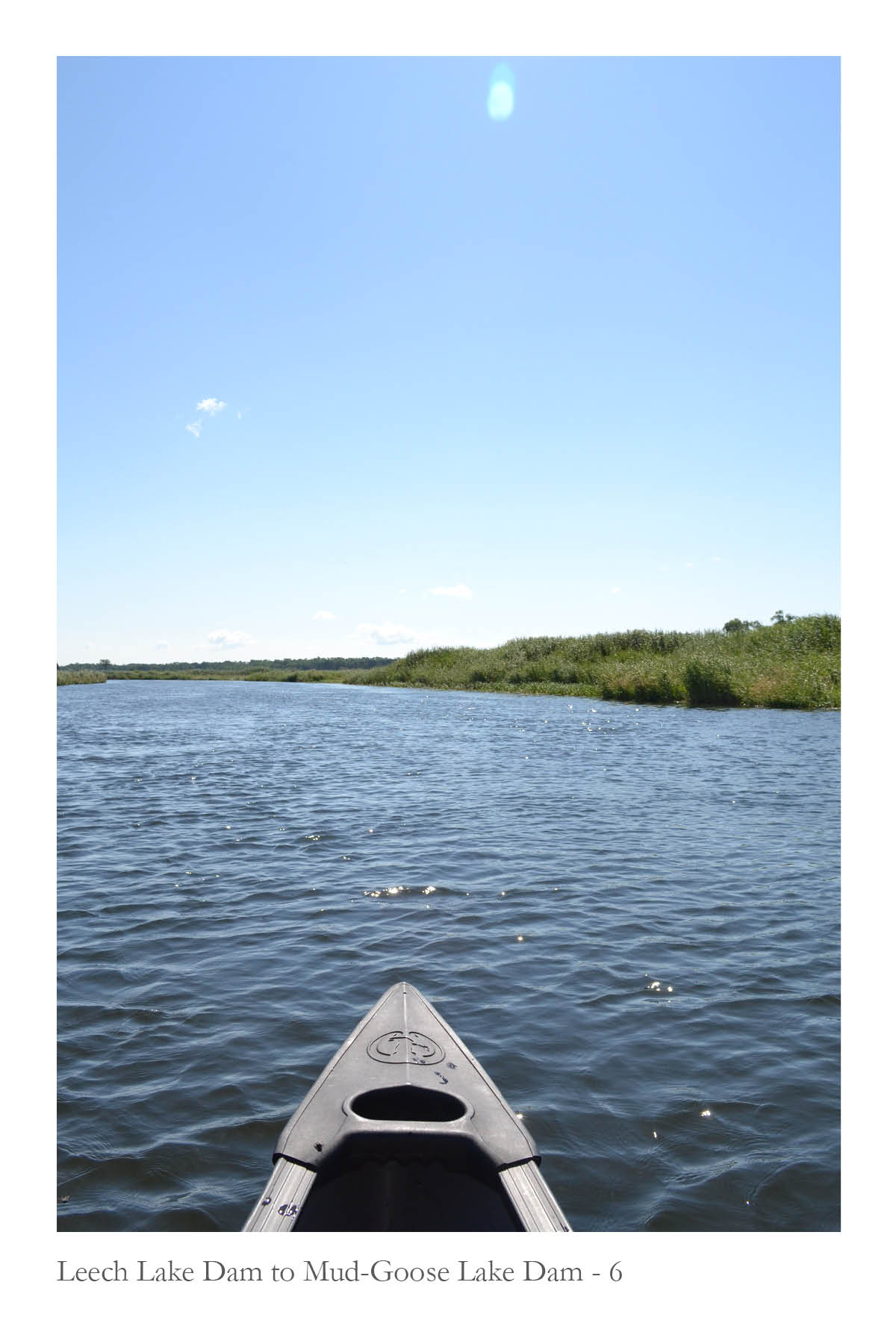

Leech Lake Dam to Mud-Goose Lake Dam ︎︎︎

Winnibigoshish Dam to US Highway 2 ︎︎︎

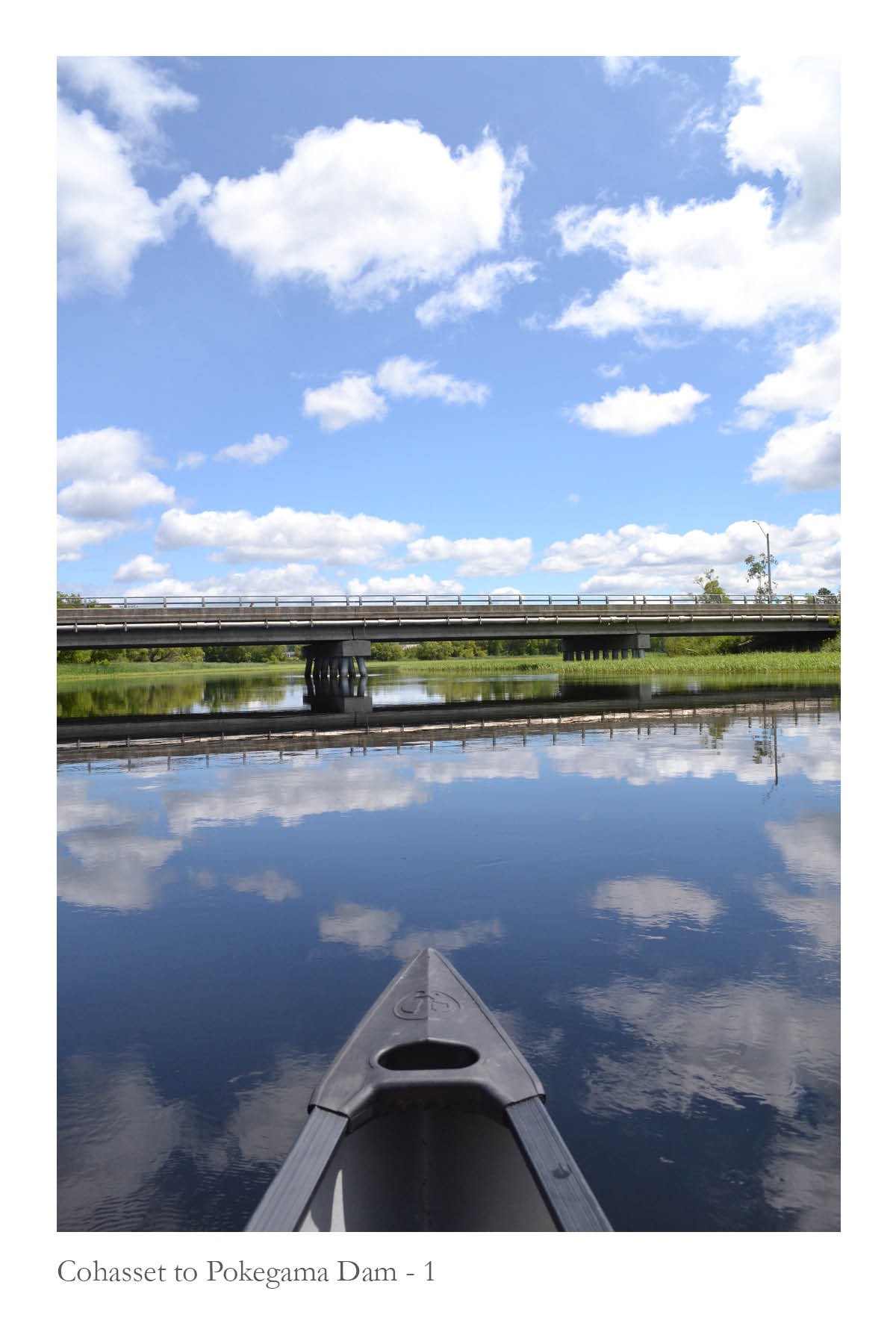

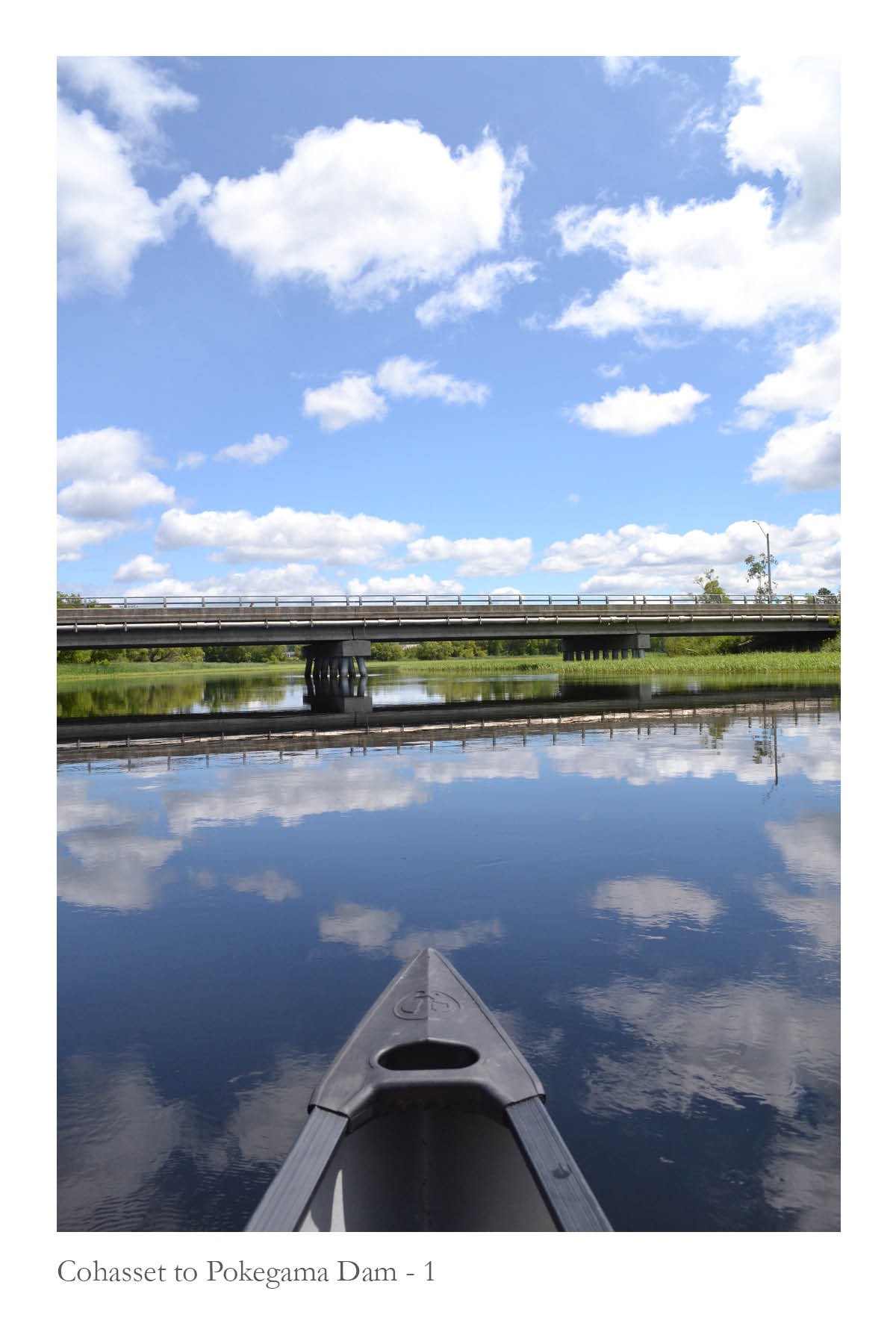

Cohasset to Pokegama Dam ︎︎︎

Environmental Impacts

︎

I —

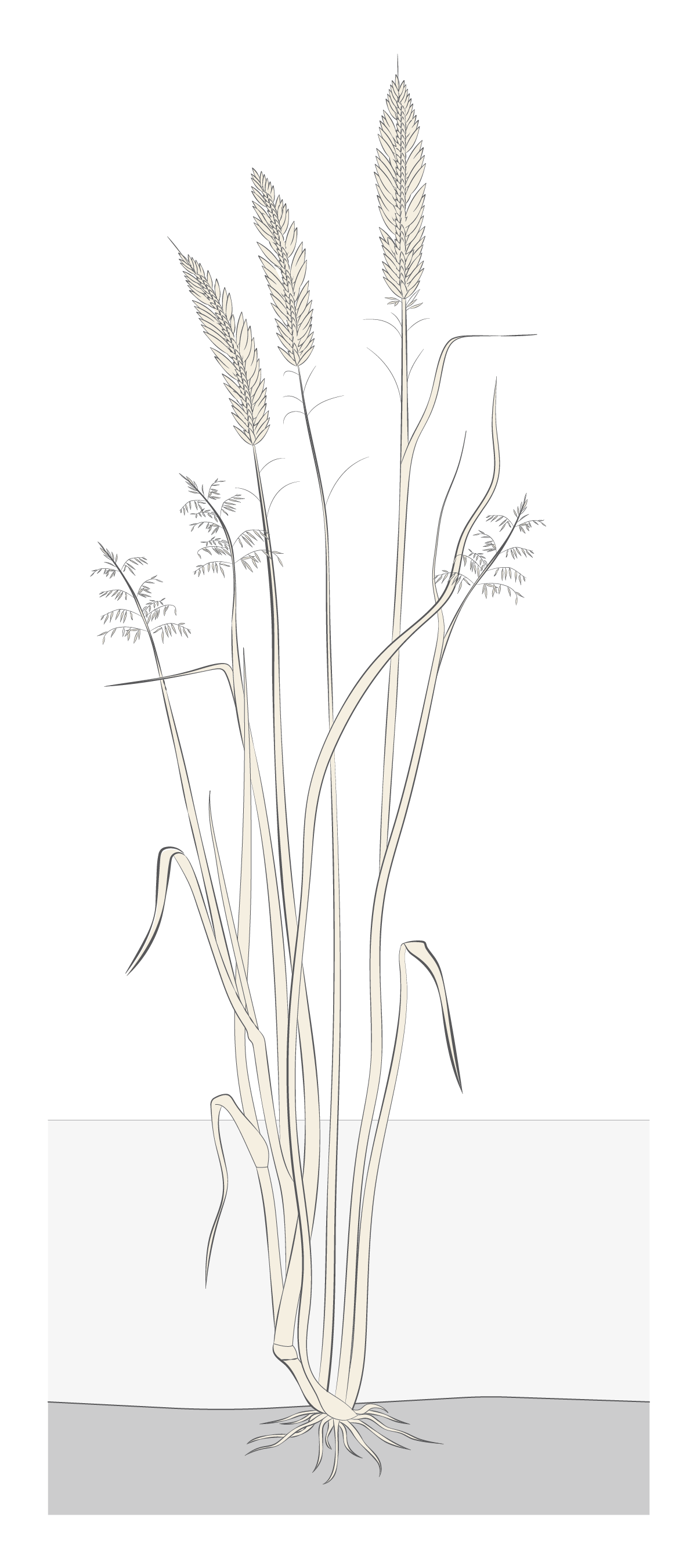

Manoomin (Wild Rice)

Manoomin, or wild rice, grows on many of the lakes and rivers in and around Leech Lake Reservation. Found in water bodies with a slight current, most manoomin grows in the shallow edges of rivers, streams, wetlands, and lakes. While gradual water fluctuations can be tolerated, rapid changes in water levels inhibit growth.

Given these characteristics, dams may impact manoomin habitat. When dams were first constructed, they raised water levels on Leech Lake, Lake Winnibigoshish, and Pokegama Lake (as well as other lakes in the area) by several feet, changing the range of shallow waters where manoomin can grow. Today, dam operation continues to impact manoomin. For example, dams can detain heavy rain from flowing downstream, raising water levels in the reservoirs where manoomin is growing. Alternatively, demand for water downstream can cause dam operators to release water from the reservoirs rapidly, again changing water levels in the lake and river edges where manoomin grow.

Another key aspect that impacts manoomin health is water quality. The Leech Lake Division of Resource Management has taken the lead in monitoring water quality by taking water samples throughout the area, as well as conducting surveys using aerial photography to monitor where wild rice is growing and how its range compares from year to year.

While manoomin still grows abundantly in some areas of Leech Lake Reservation, it has been threatened by dams in the past and continue to require monitoring, inter-governmental coordination, and activism by Ojibwe people to sustain its habitat.

II —

Erosion

Lake Shore Erosion

Dams have increased water levels in preexisting lakes, causing water to spread over land that was previously vegetated. The sandy soil and sandstone that are common to the region are easily erodible, requiring reinforcement to prevent wave action from destabilizing the shoreline.

Dams have increased water levels in preexisting lakes, causing water to spread over land that was previously vegetated. The sandy soil and sandstone that are common to the region are easily erodible, requiring reinforcement to prevent wave action from destabilizing the shoreline.

Dredged Material

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) placed material dredged from river bottoms immediately adjacent to the river. This sandy soil is often loosely packed and is eroding in many locations, with water flow pulling earth from the bottom of mounds and causing soil slumps.

Impact on Vegetation

Erosion also occurs on sites where no dredging occurs. Here, mature vegetation can collapse as soil is washed away by the river’s current.

Erosion also occurs on sites where no dredging occurs. Here, mature vegetation can collapse as soil is washed away by the river’s current.

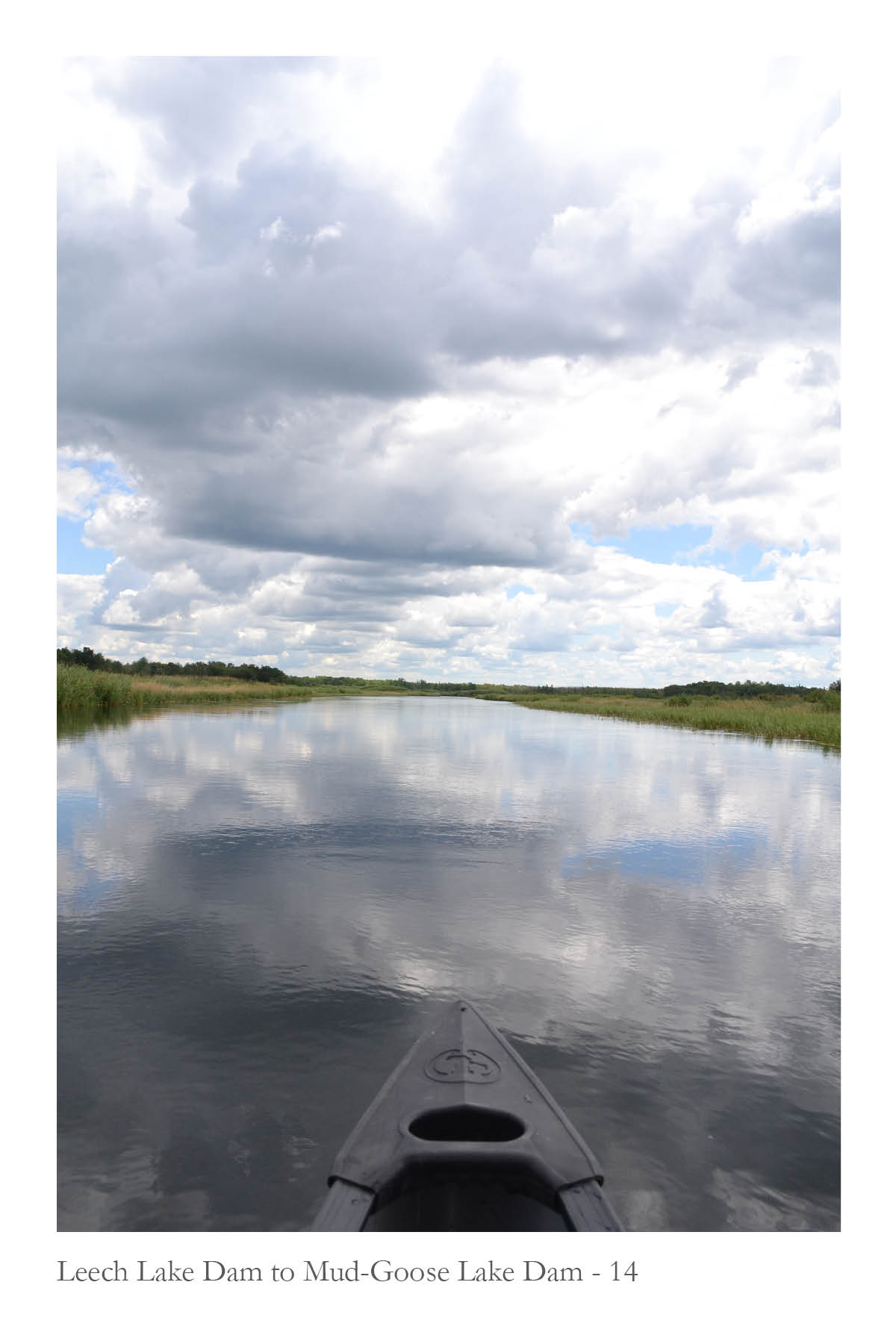

Soil Susceptibility

Many soils in the riparian corridors of the Mississippi Headwaters are sandy and susceptible to erosion.

Many soils in the riparian corridors of the Mississippi Headwaters are sandy and susceptible to erosion.

III — Dredging

To achieve regular water flow, minimize obstructions in the river, and maintain minimum depths for boat passage, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged significant portions of Leech Lake River between Leech Lake and Goose Lake, as well as the Mississippi River between Lake Winnibigoshish and the town of Grand Rapids, MN. The survey and proposed dredging locations are illustrated in the “Survey of the Mississippi River” by the Mississippi River Commission for the 62nd Congress between 1911 and 1913.

As can be seen in the excerpt from the survey above, the dredged river path also minimized meanders an shortened the river’s overall length. This, in turn, shortened the time it took for logs harvested from forestry to travel downstream.

Today, the material dredged from the river remains present in the landscape in the form of steep mounds of soil that line the rivers’ edges. The drumlin-like mounds stand out in the otherwise flat, marshy surroundings.

VIEWS FROM THE RIVER

︎

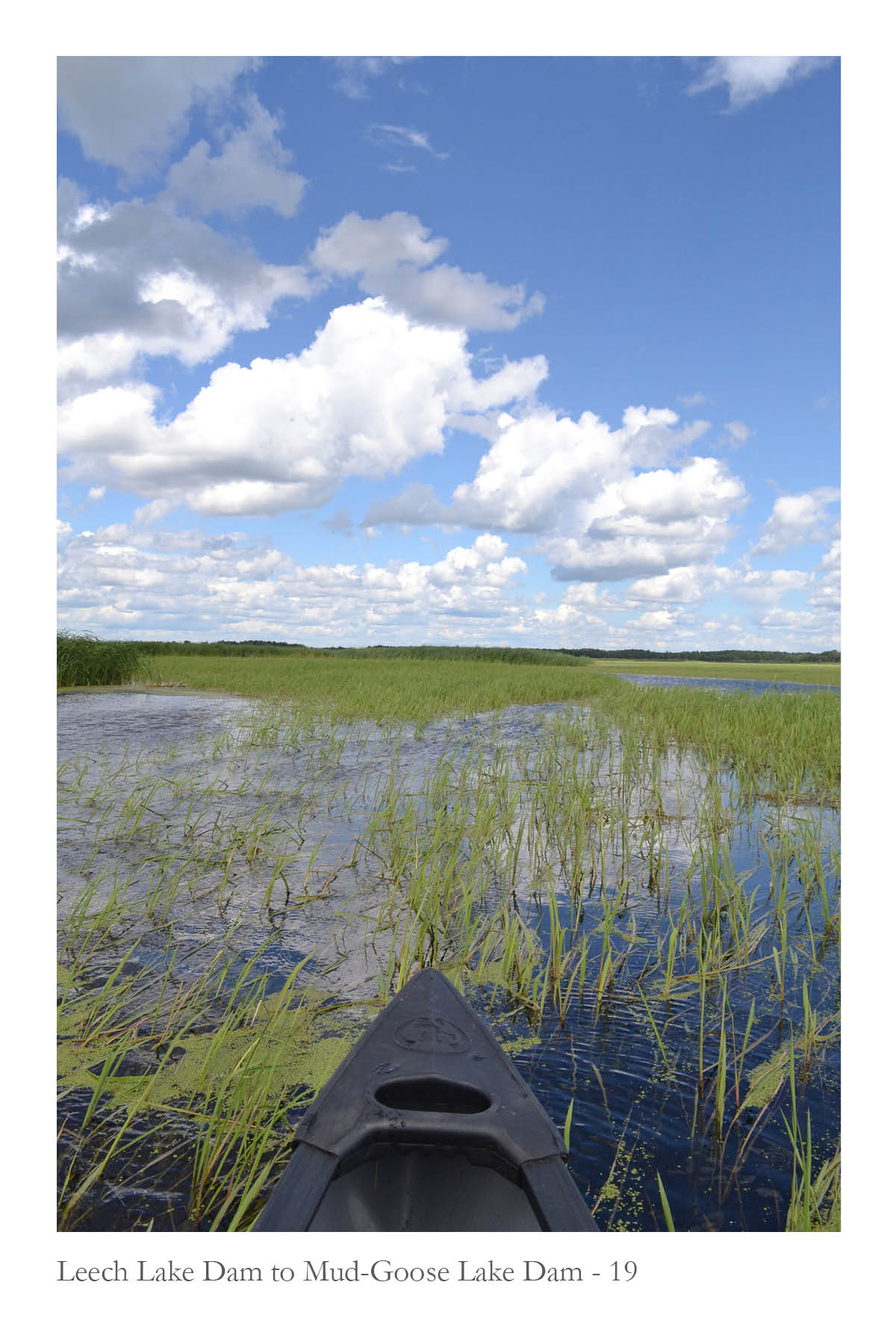

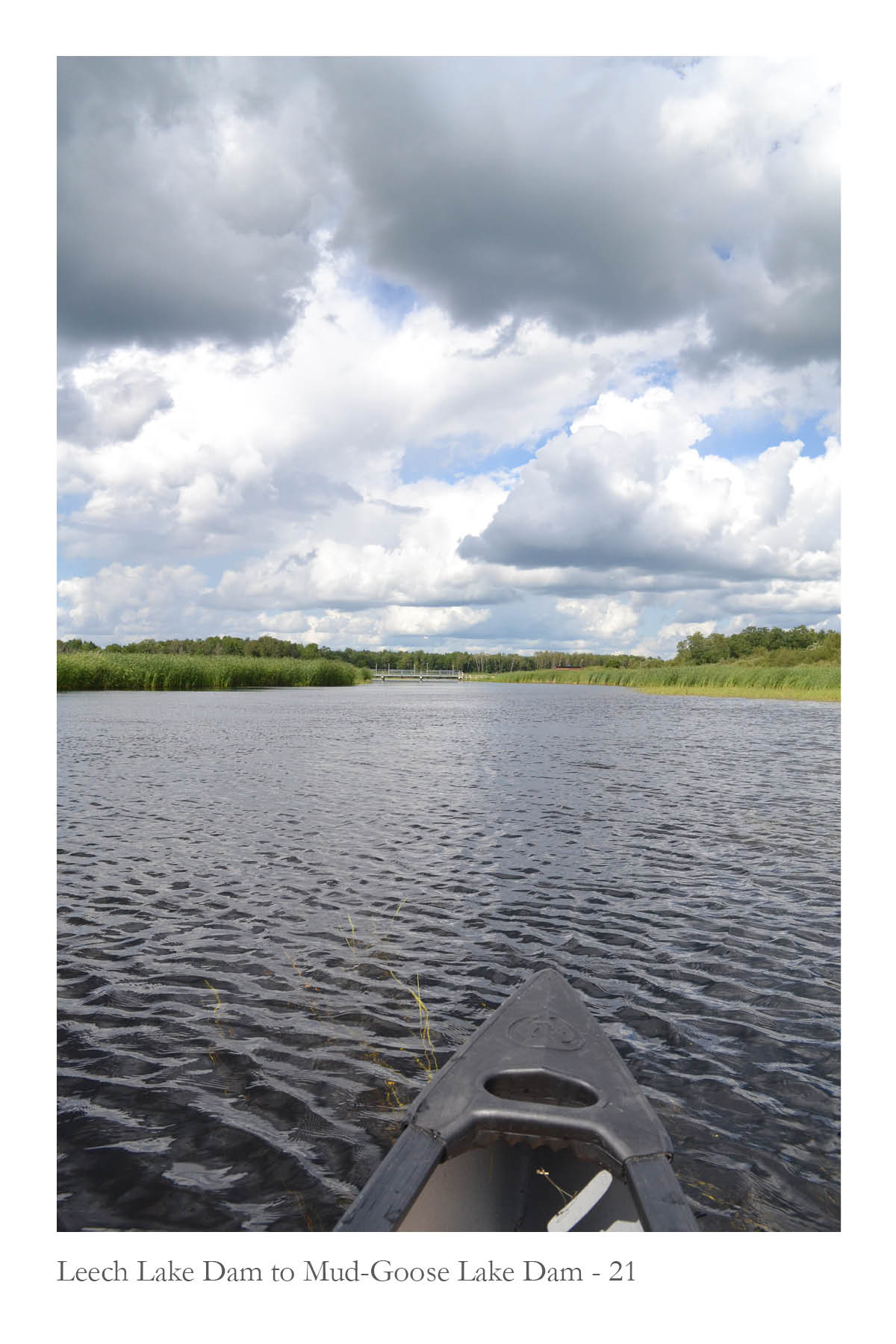

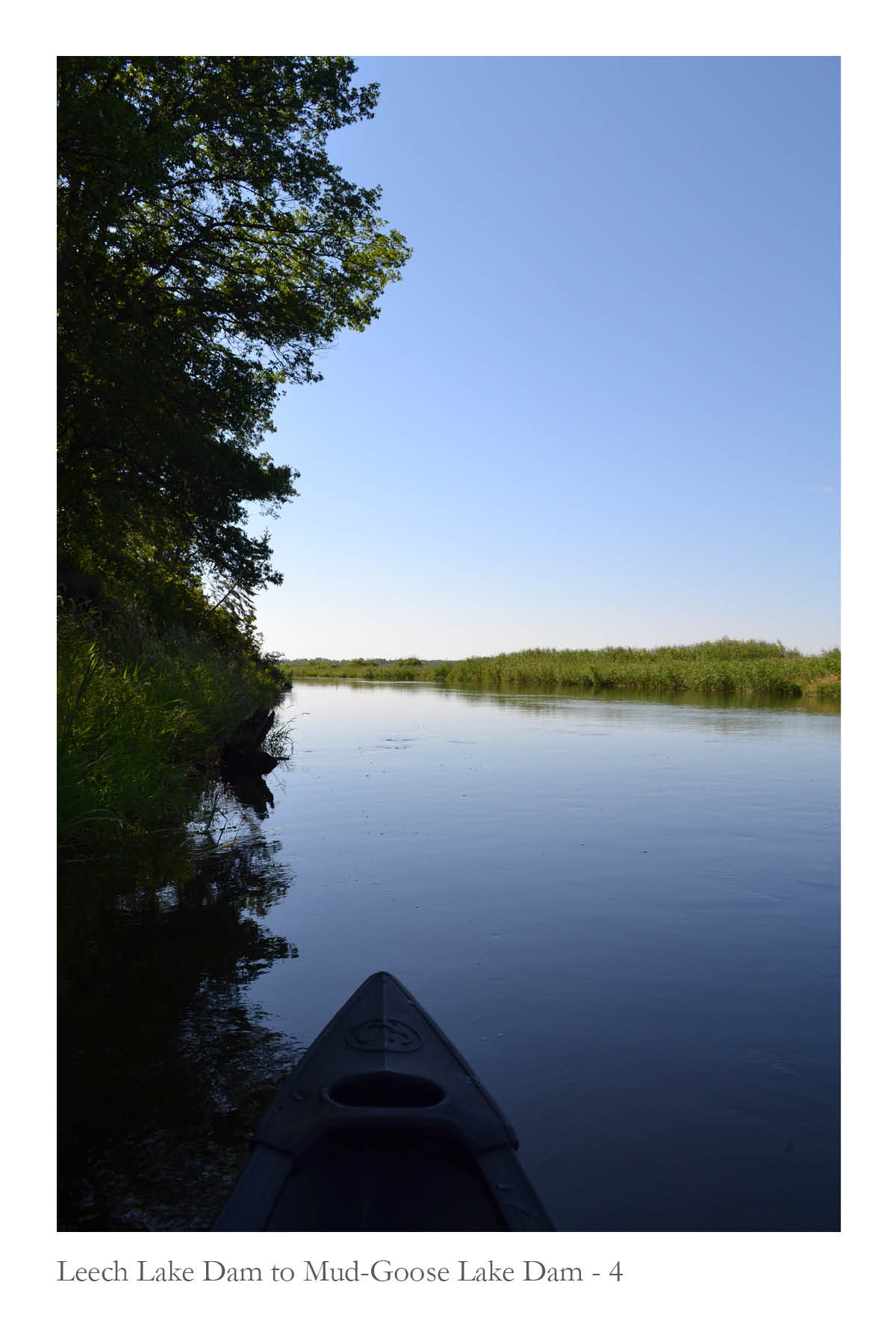

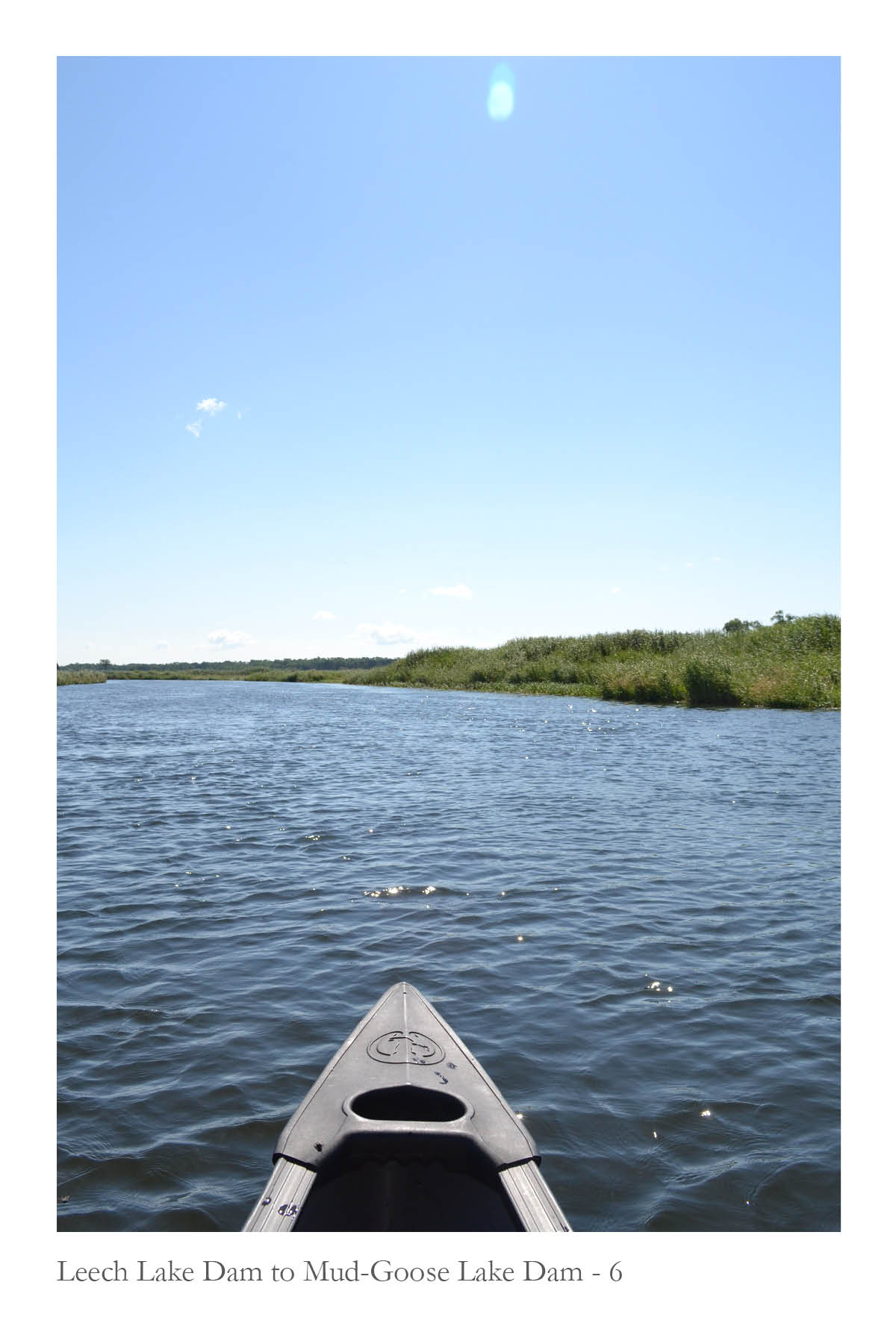

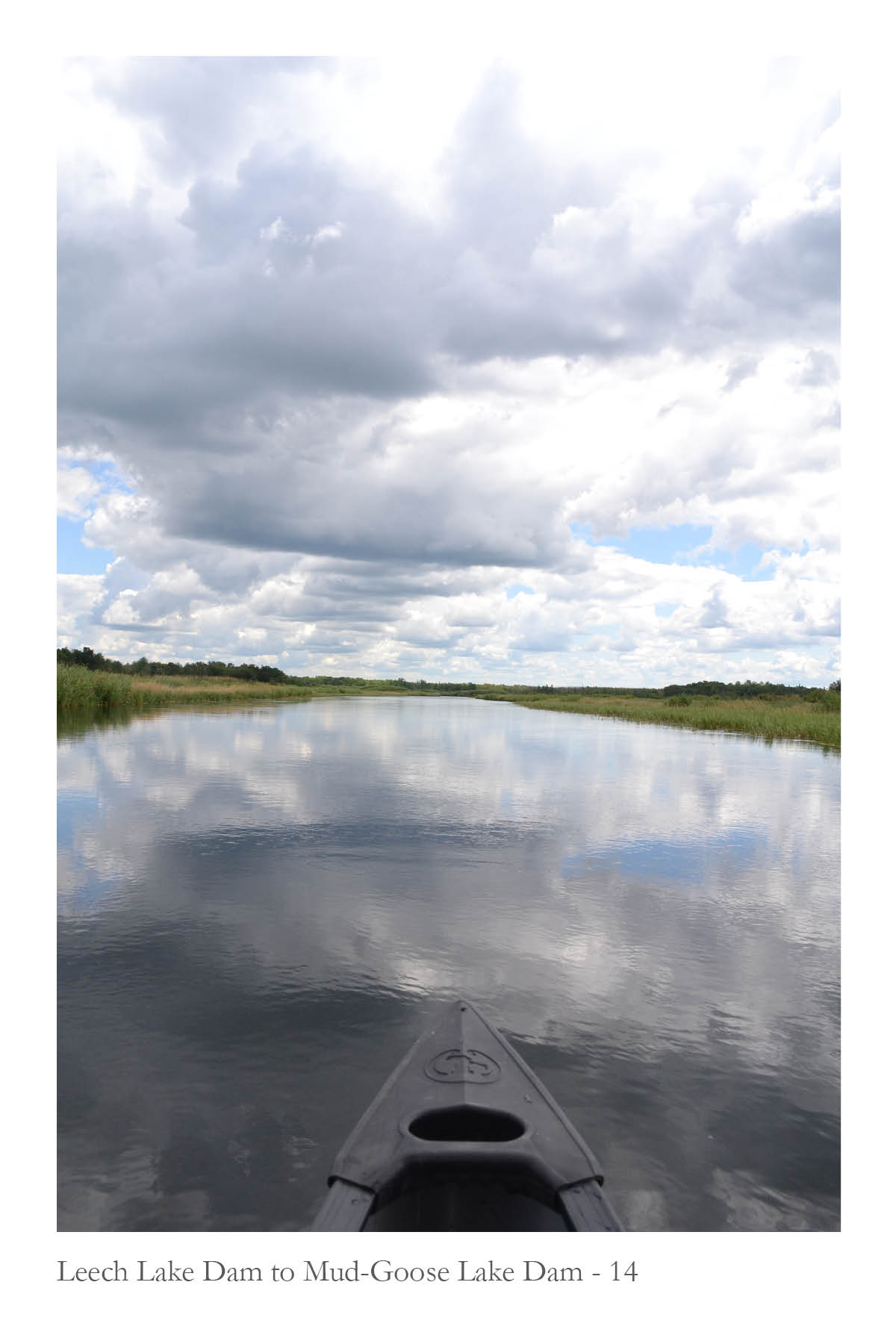

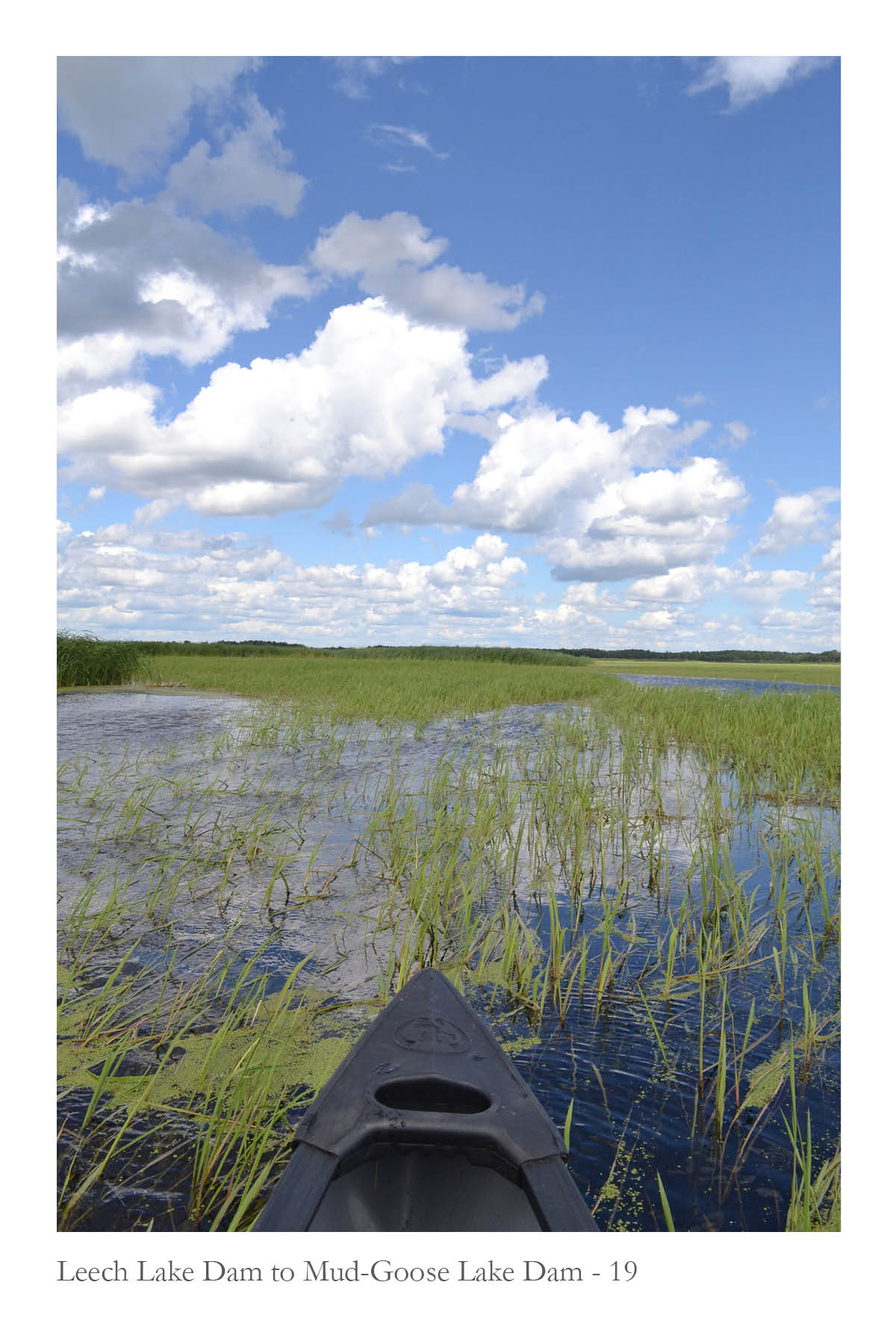

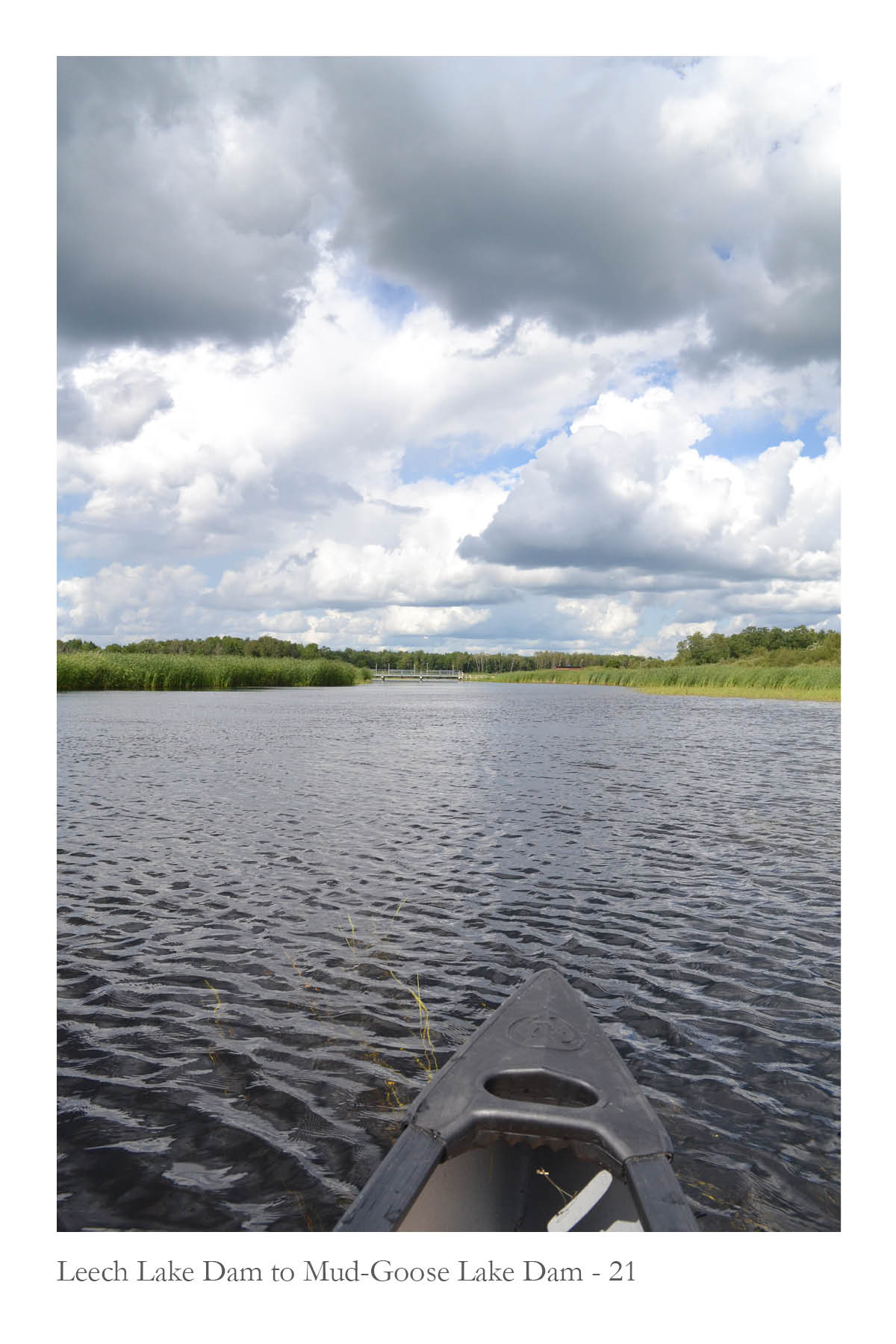

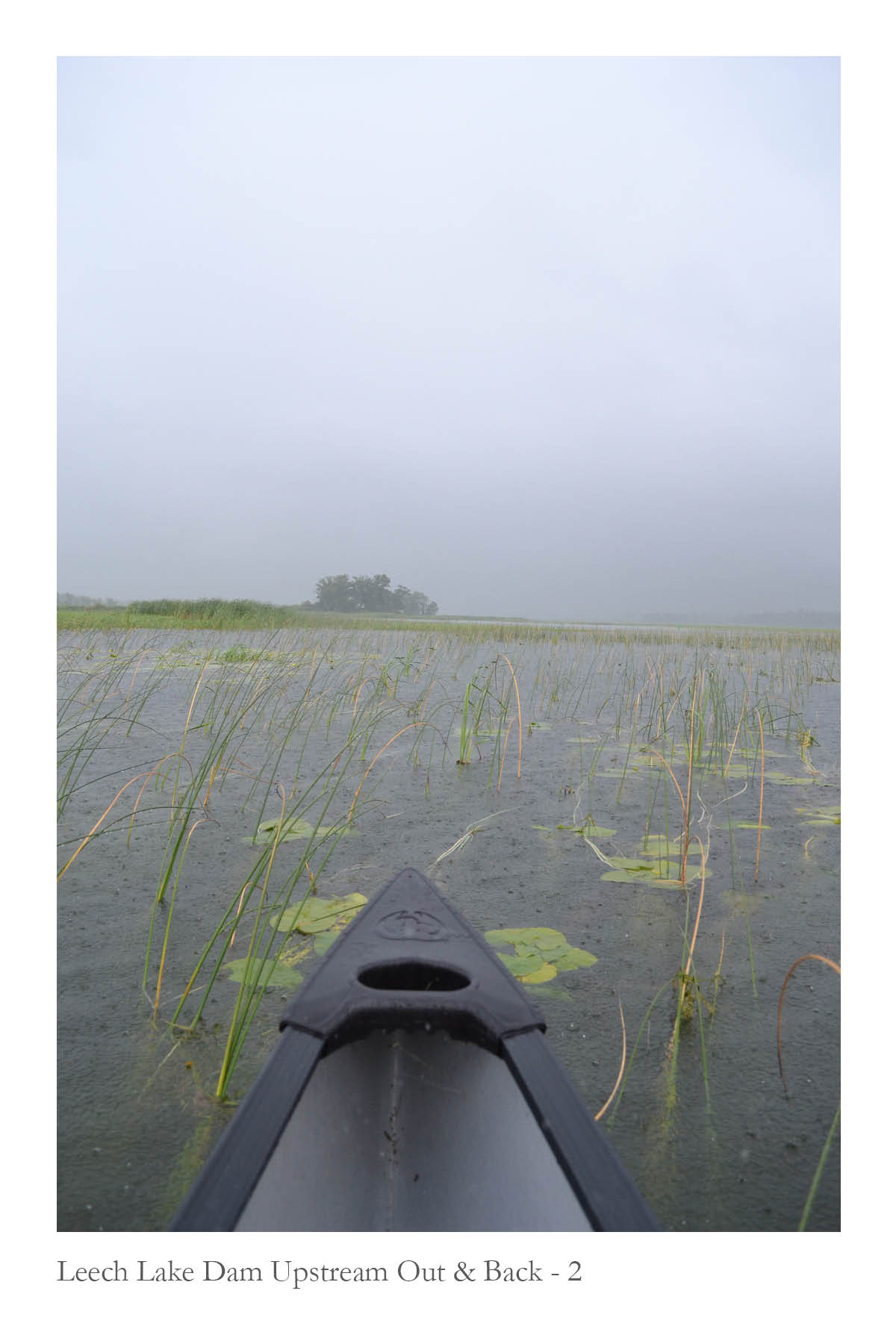

Serial Photography

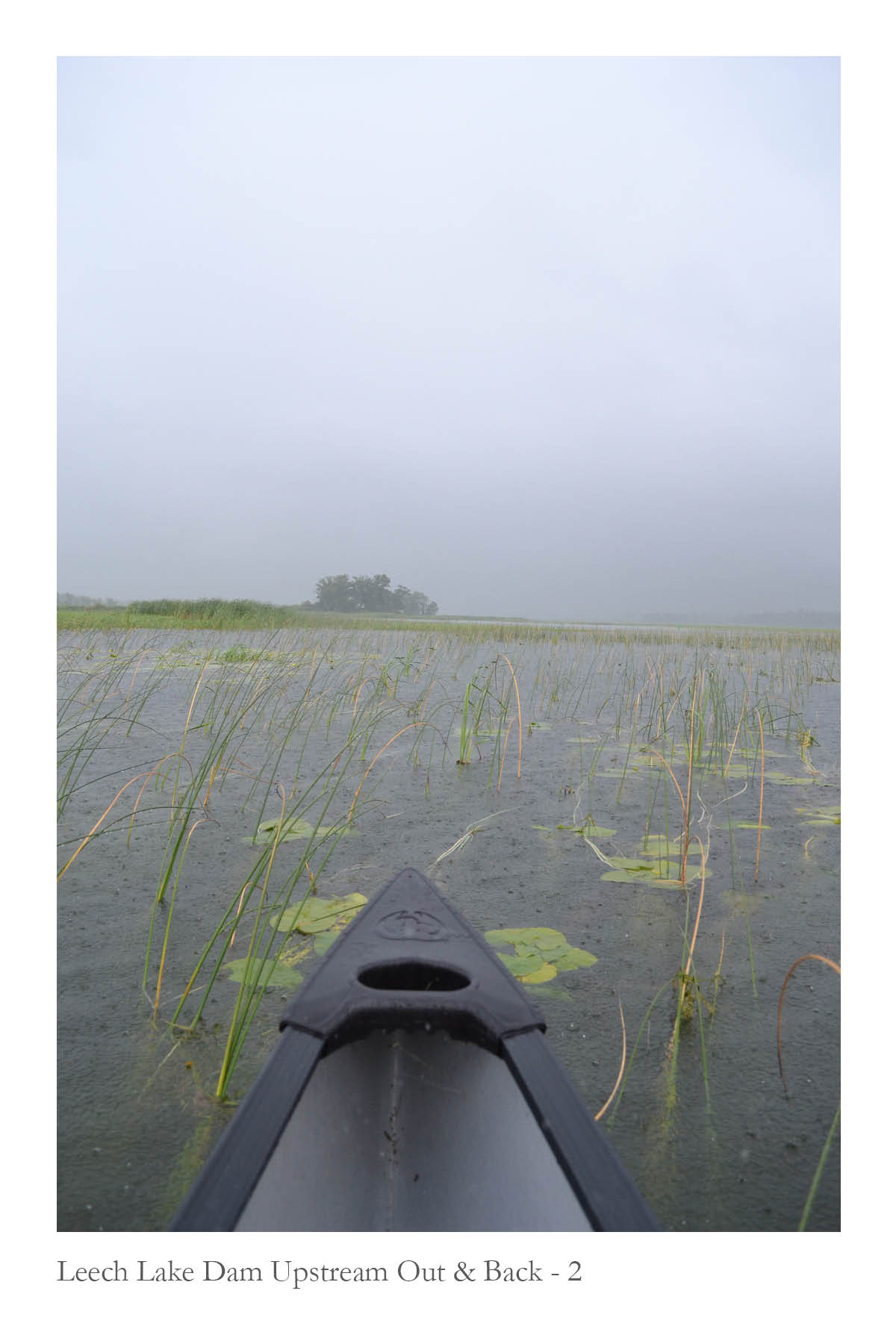

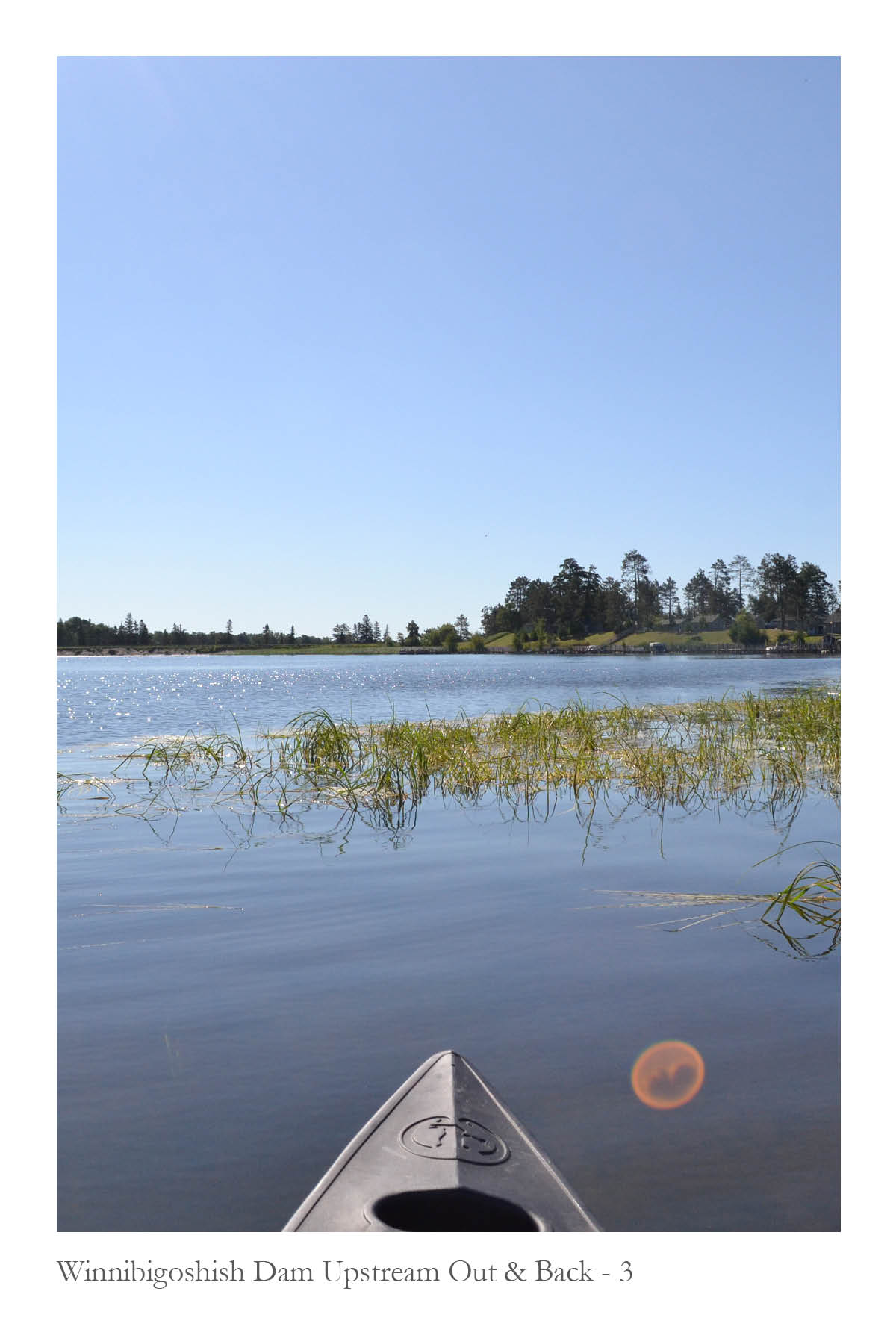

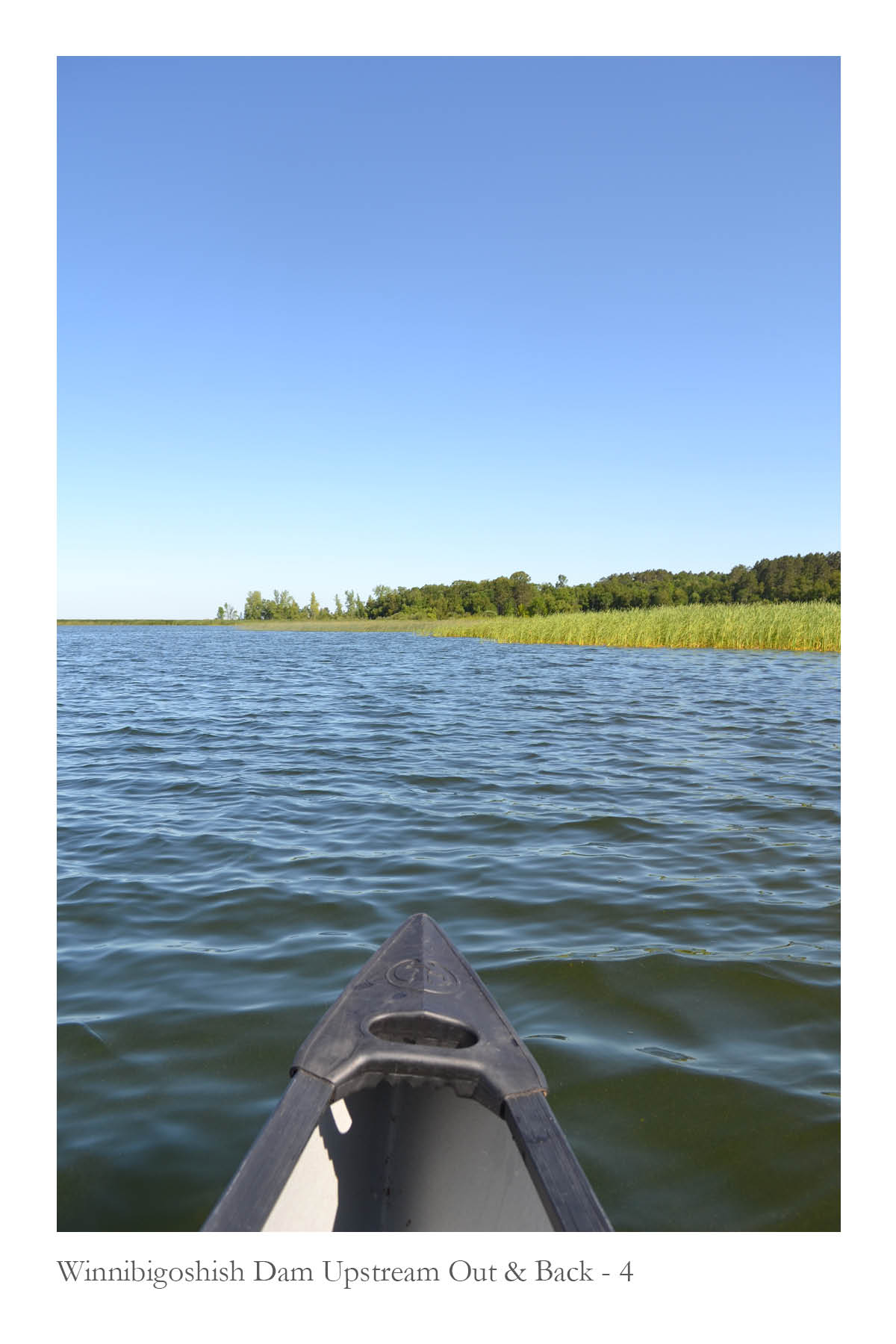

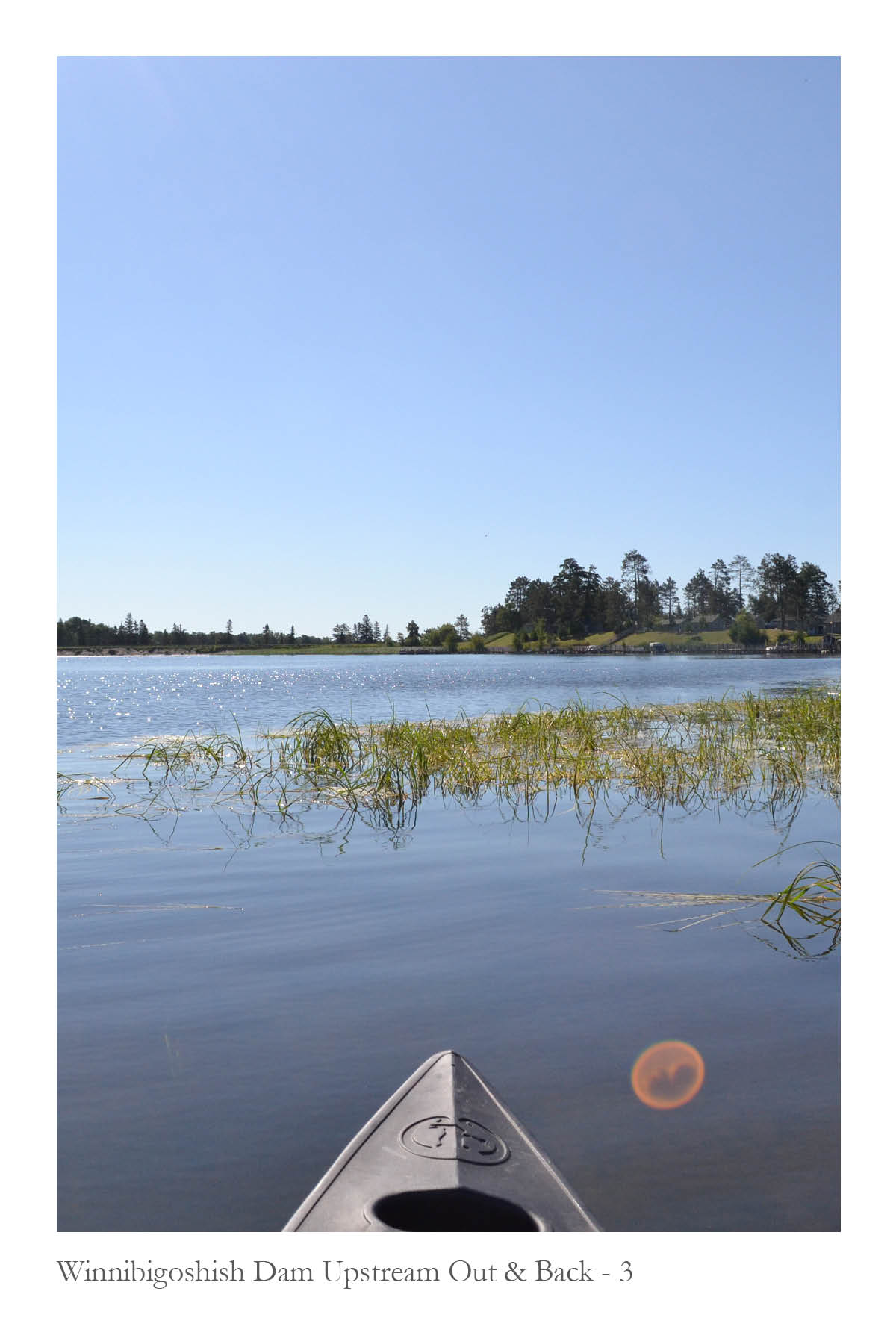

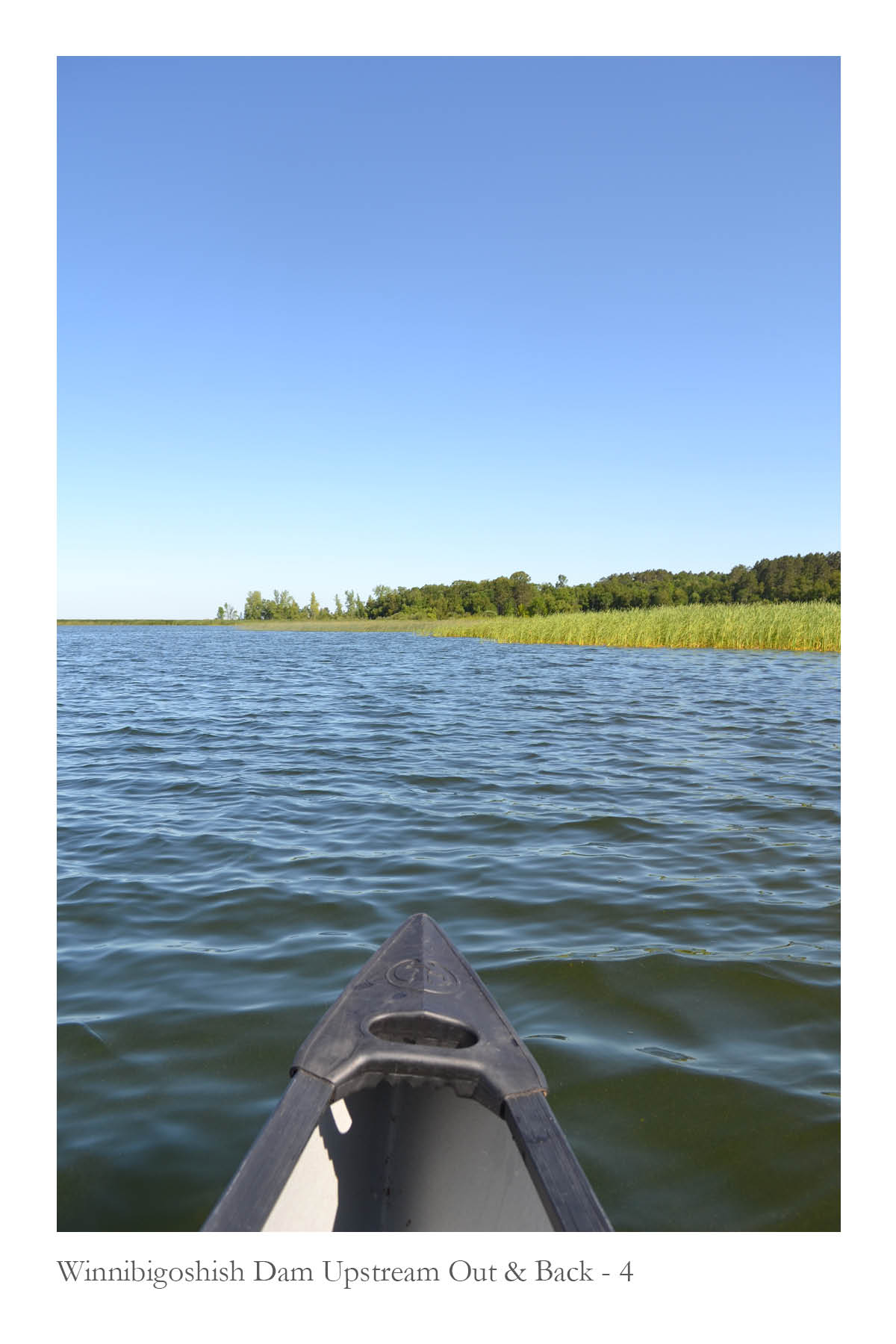

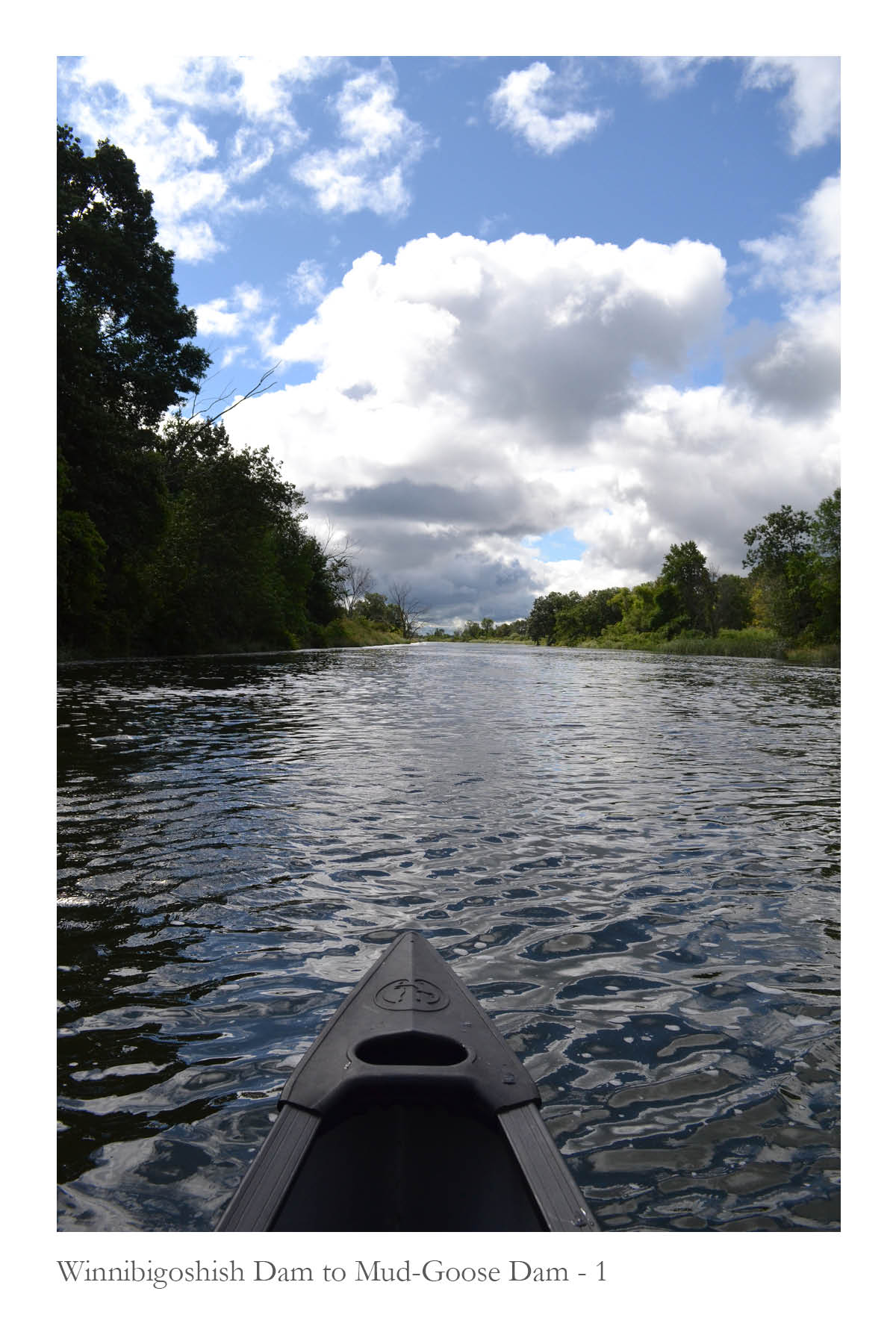

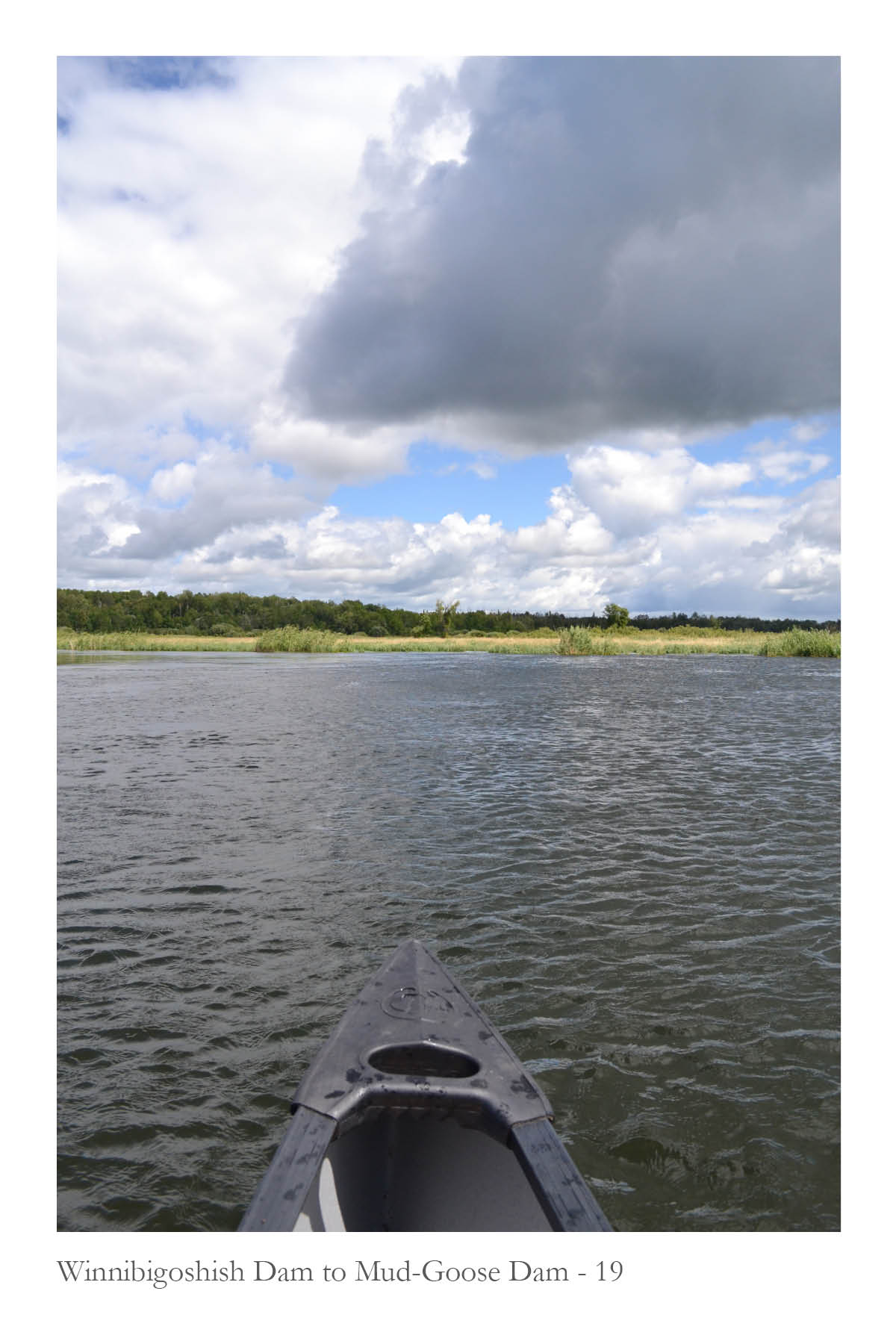

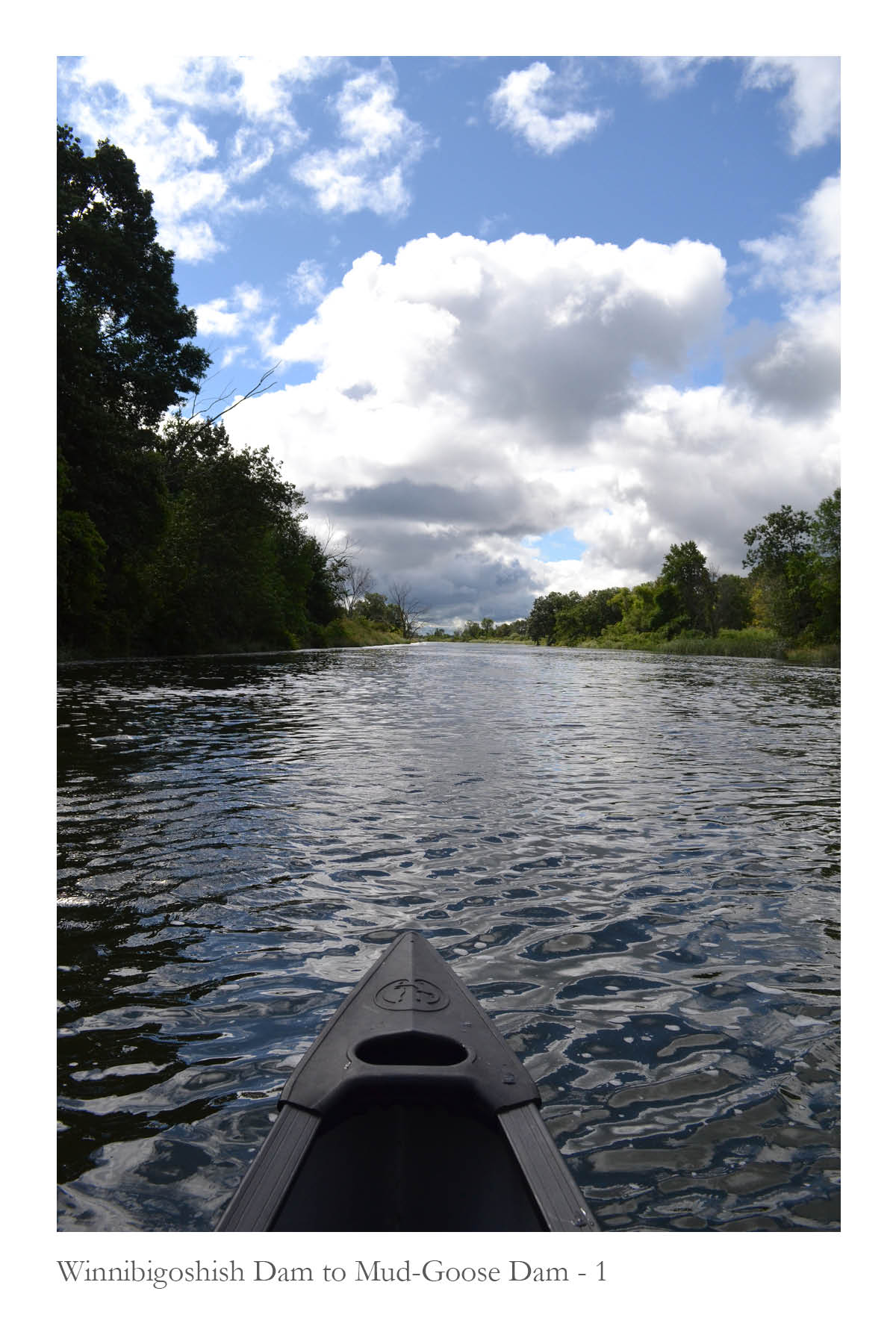

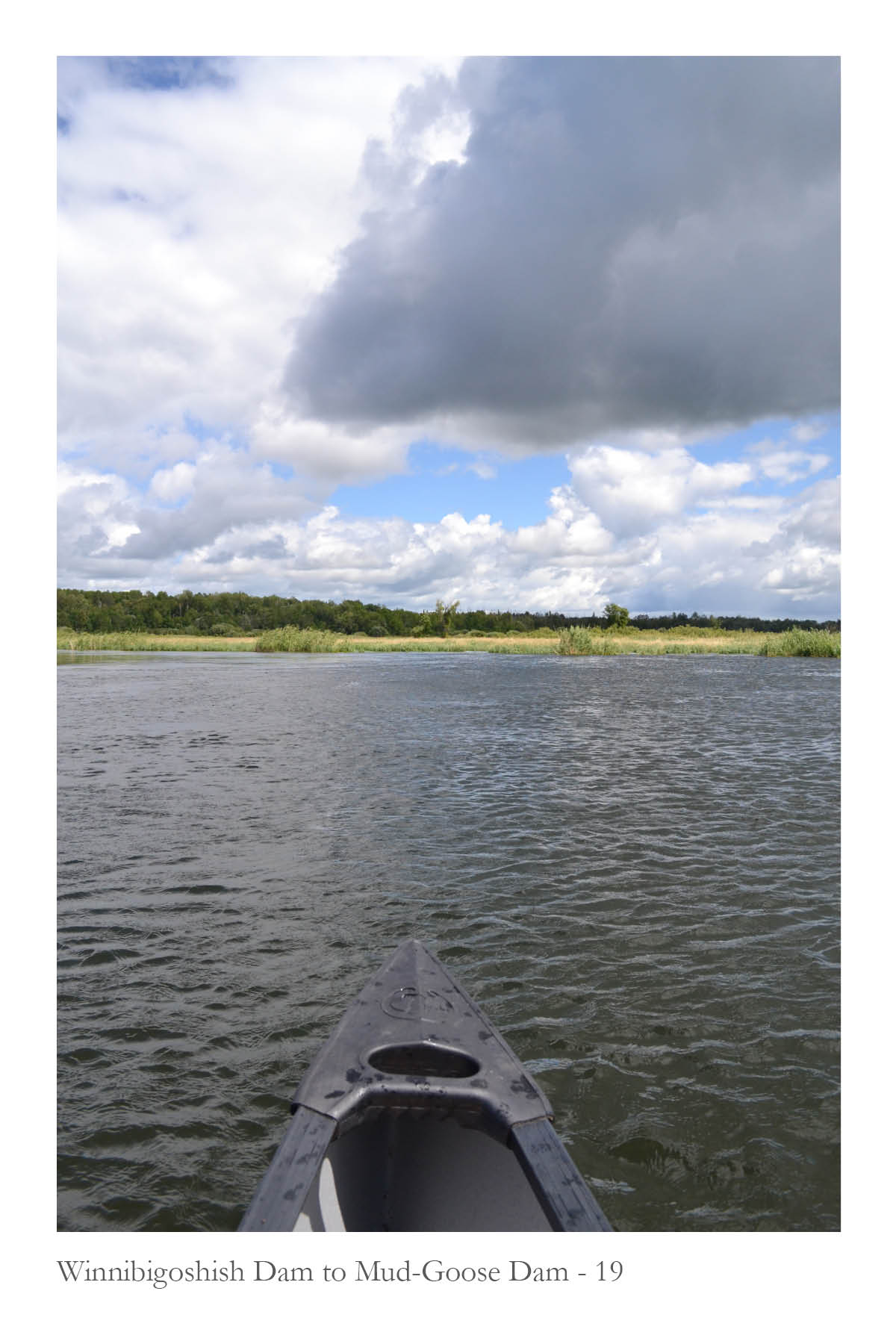

The images at right were taken on two of the longer canoe trips traveling downstream from Leech Lake Dam and Mud-Goose Lake Dam. Photographs were taken at fifteen minute increments, always oriented directy in the direction of travel and centered on the horizon line.

These images illustrate the changing riparian habitat along each river, including wetlands, mounds from dredging, forests, and small cliffs. They also reveal the meandering experience of traveling by canoe . . . sometimes at the center of the river, sometimes along the edges, or moving through patches of wild rice.

These images illustrate the changing riparian habitat along each river, including wetlands, mounds from dredging, forests, and small cliffs. They also reveal the meandering experience of traveling by canoe . . . sometimes at the center of the river, sometimes along the edges, or moving through patches of wild rice.

Leech Lake Dam to Mud-Goose Lake Dam

Downstream

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Downstream

Leech Lake Dam

Upstream Out & Back

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Upstream Out & Back

Winnibigoshish Dam

Upstream Out & Back

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Upstream Out & Back

Winnibigoshish Dam to Mud-Goose Dam

Downstream

Downstream

Cohasset to Pokegama Dam

Downstream

Downstream